The Least-Loved Type of Memoir

5 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

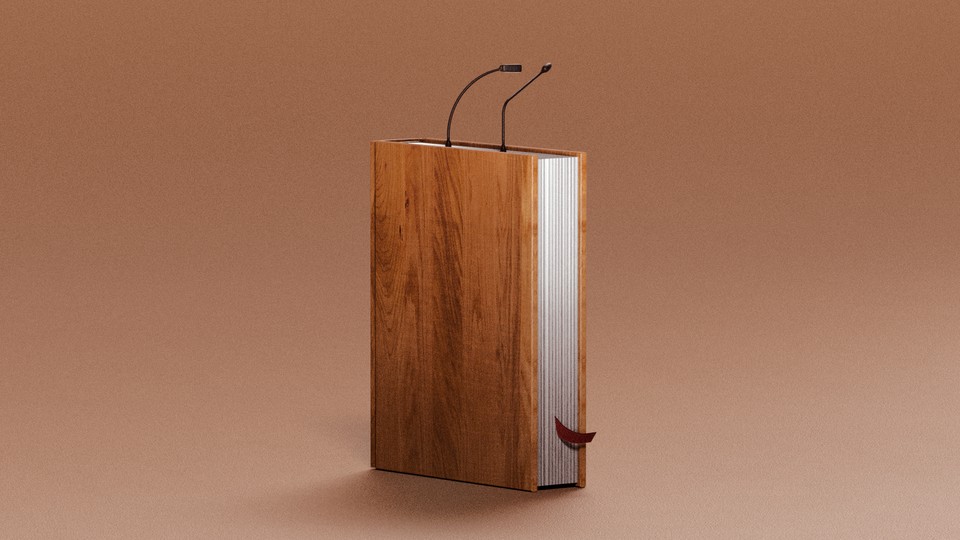

The goal of writing a memoir is to excavate one’s essential humanity, then share it with readers … except when it’s not, of course, which is often. Many—maybe most!—memoirs are published not as a means of artistic expression but instead to sell something, boost the author’s profile, capitalize on 15 minutes of fame, or win over public opinion. This is especially true of those written by famous people, and possibly most applicable to one subgenre: the politician’s book.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- Why Randy Newman is least loved for his best work

- Michel Houellebecq has some fresh predictions. Be afraid.

- The domestic thriller that shatters Chilean myths

- A dissident is built different

Every election season, as Franklin Foer noted this week, readers are inundated with a glut of titles that are, as a rule, “devoid of psychological insights and bereft of telling moments … They are, really, a pretext for an aspirant’s book tour and perhaps an appearance on The View—in essence, a campaign advertisement squeezed between two covers.” As a result, candidates running for major office usually have a book or two under their belt. Less than two weeks from this year’s presidential contest, voters are probably not best served by reading Kamala Harris’s 2019 memoir, The Truths We Hold, or any of Donald Trump’s many books (including his most influential, The Art of the Deal, whose ghostwriter, Tony Schwartz, has been publicly atoning for his role in Trump’s rise since his first presidential campaign). J. D. Vance’s best-selling Hillbilly Elegy might display a bit more literary ambition than either of those titles, but the man depicted in that 2016 book is a far cry from who Vance is in 2024. The same year he published his memoir, Vance called Trump “cultural heroin” in The Atlantic; since winning his endorsement for Senate in 2022, he has gone all in on the former president, adopting his positions and rhetoric as his own.

Still, power and politics are classic, compelling fodder for literature. And even though most election-season “quickies” lack merit, some memoirs by campaigners, activists, aides, and presidents are genuinely worthwhile, Foer writes. Michael Ignatieff’s Fire and Ashes recounts his brief career as a rising star in Canada’s Liberal Party—and the experience of crashing down to earth; Betty Friedan is “charmingly self-aware” in her memoir, Life So Far, while also exposing her “stubborn obstreperousness and an unstinting faith in her own righteousness”; Gore Vidal’s “magnificently malicious memoir” Palimpsest is, in part, a description of just how much Vidal lacked the right qualities for office. (One major disqualification: “He lived to feud.”) The six books on Foer’s list are distant from the present moment, but each is clear-eyed about the forces involved in a momentous election. One of them might be the right companion for you in the days until we have a new president-elect. I’m especially drawn to Ferdinand Mount’s Cold Cream. According to Foer, it touches on politics only for a moment, but that slice is both caustic and delightful.

Six Political Memoirs Worth Reading

By Franklin Foer

Hackish campaign memoirs shouldn’t indict the entire genre—there are truly excellent books written about power from the inside.

Read the full article.

What to Read

Still Life With Oysters and Lemon: On Objects and Intimacy, by Mark Doty

For Doty, a poet, attention is a form of secular faith: “A faith that if we look and look we will be surprised and we will be rewarded,” he explains, “a faith in the capacity of the object to carry meaning, to serve as a vessel.” In his 2001 memoir, Doty’s gaze lingers on great paintings and ordinary household objects alike. On a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Doty stands reverentially before a Dutch still life, where a lemon is rendered in luminous detail: “that lovely, perishable, ordinary thing, held to scrutiny’s light.” Then there’s the half-carved violin decorating the home he shared with his partner, Wally, “like music emerging out of silence, or sculpture coming out of stone.” These object memories are tinged with loss: Wally spent the last years of his life in their home, dying from AIDS. But Doty’s memoir reminds us that the death of a loved one doesn’t extinguish the beauty and joy of the world. “Not that grief vanishes—far from it,” he writes, but “it begins in time to coexist with pleasure.” Close observations can be a source of intimacy and contemplation: They are “the best gestures we can make in the face of death.”

From our list: Six books that will jolt your senses awake

Out Next Week

📚 Dangerous Fictions, by Lyta Gold

📚 This Motherless Land, by Nikki May

📚 Every Valley: The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times That Made Handel’s Messiah, by Charles King

Your Weekend Read

Why People Itch, and How to Stop It

By Annie Lowrey

During the day, I pace. Overnight, when the itching intensifies, I balance frozen bags of corn on my legs or dunk myself in a cold bath. I apply menthol, whose cold-tingle overrides the hot-tingle for a while. I jerk my hair or pinch myself with the edges of my nails or dig a diabetic lancet into my stomach. And I scratch.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.