Mitch McConnell’s Worst Political Miscalculation

9 min read

After the Capitol riot was finally contained on January 6, 2021, Mitch McConnell spoke from the Senate floor in unambiguous terms. The Senate, said the then–majority leader, would do its duty “by the book,” and not be deterred by the violent mob’s attempt at intimidation. McConnell said that the rioters had failed in their attempt to disrupt American democracy. The Senate affirmed Joe Biden’s election, but the American catechism of a peaceful transfer of power had been sullied.

This was a moment of moral clarity for McConnell about the threat of Donald Trump, but not a lasting one. Rather, it was merely a prelude to the kind of contradiction that has marked his time as one of the nation’s most powerful leaders.

McConnell made up his mind on Trump well before January 6. He and Trump had not spoken since a month after Election Day, when Trump yelled at McConnell for acknowledging the obvious, that Joe Biden had been fairly elected after the Electoral College vote. Trump’s “postelection behavior was increasingly detached from reality,” McConnell told me, “and it seems to me he made up this alternate universe of how things happened.” Trump, he said, had engaged in a “fantasy” that he had somehow won, and had been listening to “clowns” who served as his private lawyers.

In an interview with an oral historian in late December 2020, he called Trump a “despicable human being” and said he was “stupid as well as being ill-tempered.” Trump’s behavior after the election, McConnell said, “only underscores the good judgment of the American people. They’ve just had enough of the misrepresentations, the outright lies almost on a daily basis, and they fired him. And for a narcissist like him, that’s been really hard to take.”

January 6, McConnell told the historian the following week, was a “shocking occurrence and further evidence of Donald Trump’s complete unfitness for office.” Reflecting on the trauma of that day, McConnell said, “It’s hard to imagine this happening in this country, such a stable democracy we’ve had for so long, to have not only the system attacked but the building itself attacked.” He added later, “It was very disturbing.” He was sickened by the damage done to the Capitol itself. “They broke windows,” McConnell said. “They were narcissistic, just like Donald Trump, sitting in the vice president’s chair taking pictures of themselves.”

Calls quickly came to investigate the cause of the riot. Polls showed that a majority of Americans supported an inquiry. The House passed bipartisan legislation to create a commission modeled after the one that had examined the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, a body that would include an equal number of Democrats and Republicans. Thirty-five Republicans in the House joined Democrats to support the measure.

Then the legislation went to the Senate, and McConnell pivoted. Congressional committees, he said, were capable of conducting the investigation, and the commission was largely a Democratic ploy to “relitigate” that day and Trump’s role in it. So on May 28, less than six months after his own life had been jeopardized during the riot, he blocked perhaps the nation’s best chance at getting a full accounting of what had happened.

McConnell was well aware that he would be criticized, and, as at so many other times during his tenure in the Senate, he did not let that deter him from his larger goal. He had said a few weeks earlier that his focus was to thwart Biden’s agenda “100 percent.” McConnell’s best shot at making good on that threat would be to regain just one seat in the Senate in the 2022 midterms, retaking the majority for Republicans and restoring him to the position he coveted.

Abandoning the commission could readily be seen as a craven concession to his party’s right flank, but McConnell has an unsentimental view of tactics and strategies that do not lead to victories and majorities. McConnell blocked the inquiry by deploying the filibuster and requesting the support of some Republicans, such as Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, as a rare “personal favor” to him. McConnell was worried Trump would encourage more fringe candidates, the kind who had doomed Republican hopes in previous elections. If Trump were not a unifying force in the midterm elections, when the president’s party typically suffers heavy losses, then Democrats would be in a position to defy history and keep power in Congress. So McConnell ignored the insults and chose what he saw as the surest path back to the majority.

More striking was how McConnell approached another potential remedy to deal with Trump: a second impeachment.

A week after the insurrection at the Capitol, McConnell noted in an oral-history interview that the House was likely to impeach Trump very soon. “Someone listening to this years from now might wonder what’s the point; he’s leaving office anyway on January 20,” he said. “But apparently you can impeach somebody after they leave office, and if that happens, there’s a second vote in the Senate, which only has to pass by a simple majority, that prevents that person from seeking office again. So he could not only be impeached, but also eliminated from the possibility of a comeback for this office. So it is significant.” While not showing his hand, he was signaling an inclination.

McConnell said that voting in the Senate before Trump left office would be difficult. He talked with Biden about the challenge of getting his Cabinet in place if the Senate was caught up in an impeachment trial. The Senate also had time off scheduled. Still, it was at least theoretically possible to have it back in session to deal with impeachment.

“I’m not at all conflicted about whether what the president did is an impeachable offense. I think it is,” McConnell said in the oral history. “Urging an insurrection, and people attacking the Capitol as a direct result … is about as close to an impeachable offense as you can imagine, with the possible exception of maybe being an agent for another country.” Even so, he was also convinced by legal opinions that the Senate could not impeach someone after they had left office. He was not yet certain how he would vote.

Democrats pushed to impeach Trump, and the House moved quickly to do so. Up until the day of the Senate vote, it was unclear which way McConnell would go. “I wish he would have voted to convict Donald Trump, and I think he was convinced that he was entirely guilty,” Senator Mitt Romney told me, while adding that McConnell thought convicting someone no longer in office was a bad precedent. Romney said he viewed McConnell’s political calculation as being “that Donald Trump was no longer going to be on the political stage … that Donald Trump was finished politically.”

George F. Will, the owlish, intellectual columnist who has been artfully arguing the conservative cause for half a century, has long been a friend and admirer of McConnell. They share a love of history, baseball, and the refracted glories of the eras of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. On February 21, 2021, Will sent an advance version of his column for The Washington Post to a select group of conservatives, a little-known practice of his. One avid reader and recipient was Senator Bill Cassidy, Republican of Louisiana, who read this column with particular interest. Will made the case that Republicans such as Cassidy, McConnell, and others should override the will of the “Lout Caucus,” naming Lindsey Graham, Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley, Marco Rubio, and Ron Johnson among them.

“As this is written on Friday [Saturday], only the size of the see-no-evil Republican majority is in doubt.” Will harbored no doubt. He abhorred Trump. He had hoped others would vote to convict, including his friend. The last sentence of his early release was bracketed by parentheses: “(Perhaps, however, a revival began on Saturday when the uncommon Mitch McConnell voted ‘Aye.’)” Will had either been given an indication of McConnell’s vote or made a surmise based on their long association.

Cassidytold me he thought that meant McConnell had clued Will in on his vote, so he called Will on Saturday. Will told him that the column was premature, and he was filing a substitute.

His new column highlighted McConnell’s decision to vote not guilty, saying that the time was “not quite ripe” for the party to try to rid itself of Trump. “No one’s detestation of Trump matches the breadth and depth of McConnell,” Will wrote in the published version. Nevertheless, “McConnell knows … that the heavy lifting involved in shrinking Trump’s influence must be done by politics.” McConnell’s eyes were on the 2022 midterm elections.

Will told me he did not recall writing the earlier version.

On the morning of the Senate vote on impeachment, there was still some thought among both Republicans and Democrats that McConnell might vote to convict Trump. The opening of his remarks certainly suggested as much.

“January 6 was a disgrace,” McConnell began. “American citizens attacked their own government. They use terrorism to try to stop a specific piece of domestic business they did not like. Fellow Americans beat and bloodied our own police. They stormed the Senate floor. They tried to hunt down the speaker of the House. They built a gallows and chatted about murdering the vice president.

“They did this because they’d been fed wild falsehoods by the most powerful man on Earth because he was angry. He lost an election. Former President Trump’s actions preceded the riot in a disgraceful dereliction of duty … There’s no question, none, that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of the day. No question about it.”

Then-Representative Liz Cheney, who would lose her Republican primary the following year because of her criticisms of Trump, wrote in her memoir that she knew McConnell had, at one point, been firm in his view that Trump should be impeached, but she had grown concerned about his “resolve.” When Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky made a motion that the trial was unconstitutional because Trump was no longer president, McConnell voted for it, a sign to Cheney that his position was shifting.

Her concerns were borne out: McConnell held a strong belief that Trump had committed an impeachable offense but made a political decision that overrode it.

McConnell thought that Cheney had made a mistake. “Where I differed with Liz is I didn’t see how blowing yourself up and taking yourself off the playing field was helpful to getting the party back to where she and I probably both think it ought to be,” McConnell told me. He later added, “I think her sort of self-sacrificial act maybe sells books, but it isn’t going to have an impact changing the party. That’s where we differed.”

Cheney thought that it was McConnell who had abdicated his duty and responsibility to do more to rid the GOP of Trump. In a post on X, she said, “Mitch McConnell knows Trump provoked the violent attack on our Capitol … He knows Trump refused for hours to tell his mob to leave … He knows Trump committed a ‘disgraceful dereliction of duty’ … Trump and his collaborators will be defeated, and history will remember the shame of people like @LeaderMcConnell who enabled them.”

McConnell, in part to preserve his position with the Republican members and mindful of what had happened to senators such as Mitt Romney, who had become an outcast to many in his party for simply standing firm on principle, decided against voting to convict. He argued that the Constitution did not provide for such a penalty once a president had left office. There is ample debate about that point, but for McConnell, as usual, the political rationale was sufficient. Biden was among those who understood the politics. In an Oval Office interview, he told me, “I can understand the rationale—not agree with it—understand the rationale to say, ‘If I don’t do this, I may be gone.’”

McConnell’s goal was to preserve a Senate majority. He wanted the energy of Trump’s voters in Senate races, without the baggage of Trump. He gambled on his belief that Trump would fade from the political stage in the aftermath of the insurrection. Instead, Trump reemerged every bit as strong among core supporters. It was likely the worst political miscalculation of McConnell’s career.

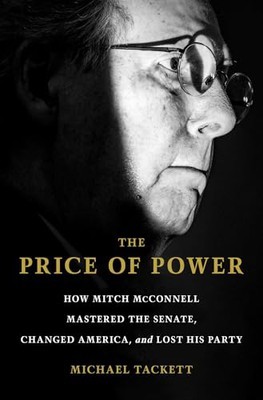

This article was adapted from Michael Tackett’s new book, The Price of Power.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.