What the Internet Age Is Taking Away From Writers

6 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

In the spring of 2013, a reporter told me, in no uncertain terms, to leave Thomas Pynchon alone. I was working on a magazine profile of the wildly inventive, extremely press-averse novelist, and the journalist on the other end of the line had once written an article about him. I knew that he had since become friendly with Pynchon; I should have inferred that because of this, he was now a dogged guardian of the author’s privacy. He also argued that the life of an artist is irrelevant, and their work is all that matters. I disagreed, and proceeded with my profile. But I also came to admire Pynchon’s cat-and-mouse game with the media. And a decade later, after watching authors tirelessly self-market online, I find myself wishing that writers still had the option to disappear.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- Richard Price’s radical, retrograde novel

- The queer author who spoke the plain truth

- “Mother of the Blues,” a poem by Christell Victoria Roach

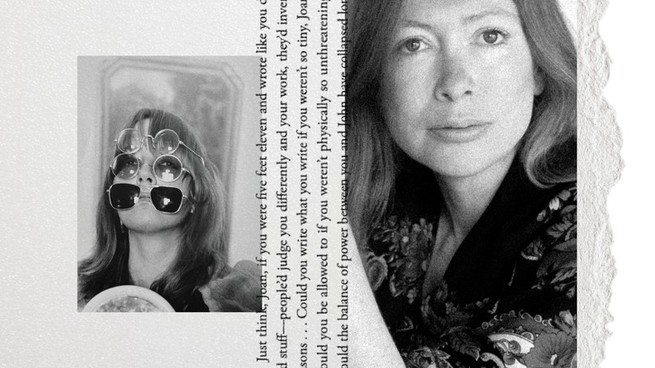

Joan Didion, by contrast, was hardly a recluse; she went to many parties, and her photographic poses—in front of a Corvette, behind Celine sunglasses—made her, literally, an icon. Yet if you saw her onstage or interviewed her at length, you came away with the impression of someone very small and very shy. This week, Lynn Steger Strong wrote about a new book, Didion and Babitz, in which the author, Lili Anolik, contrasts the lives and personalities of Didion and her fellow Los Angeles essayist, Eve Babitz. The book sprang from the discovery of a letter Babitz wrote to Didion, which deftly (if snippily) dissects Didion’s shrinking presence. “Just think Joan,” Babitz wrote, “if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff—people’d judge you differently … could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed if you weren’t physically so unthreatening?”

Didion may well have agreed with the assessment; she herself said that her ability to disappear into the Haight-Ashbury scene, which she documented in her famous essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, helped her vivisect the late-1960s counterculture. Yet Anolik’s book, Strong argues, diminishes Didion even further, using her as a foil against the warm and garrulous Babitz and casting aspersions on her private life. “One of the dangers of anecdotes, the raw material of gossip, is how easily stories can be weaponized,” Strong writes. “Almost always in Didion and Babitz, the Babitz tales grow and richen, and Didion tidbits are dropped as damning evidence.”

Anolik might well agree with that assessment. In an essay published this week in New York magazine, she admits that her book is “biased against Didion to an outrageous degree,” but pleads innocence: “The violence I committed was inadvertent.” She also compares Didion to another subject of her reporting. In her podcast Once Upon a Time … at Bennington College, Anolik traced the undergraduate years of the press-shy novelist Donna Tartt—and revealed enough to receive several letters of warning from Tartt’s attorneys.

Like Anolik, I once pursued a profile of Tartt, but when she declined to participate, I desisted. I confess that my interest in her, as with Pynchon and Harper Lee, was driven in part by how little I knew about someone whose writing I greatly admired. In her New York essay, Anolik calls her podcast “an act of love and an act of aggression.” Tartt and other writers fear that aggression most, but they also benefit from the aura of mystery that courts such intense curiosity. A private persona can draw readers to the work just as much as—perhaps even more than—a persistently public presence would.

After spending years probing authors’ lives for clues to their work—and, far more often, fielding requests from writers who would kill for an ounce of media attention—I find myself most in awe of those who insist on never explaining themselves. There is only one writer who truly fits that bill in the Instagram era: Elena Ferrante. Reporters spent years hunting down the real identity of the pseudonymous author of My Brilliant Friend, and one of them made a convincing case eight years ago. But no one much cared, because by that point, Ferrante had built an enormous following without so much as revealing her actual name. That is a truly rare accomplishment, one I’m not sure even Pynchon could pull off. It occurs to me now that the reporter I called up in search of the author wasn’t protecting Pynchon’s privacy—or not just that. He was protecting a vital source of Pynchon’s power.

Why Gossip Is Fatal to Good Writing

By Lynn Steger Strong

A new book compares the authors and frenemies Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, but its fixation on their rivalry obscures the complicated truth.

Read the full article.

What to Read

On Politics, by H. L. Mencken

Journalism rarely lasts. After all, many stories that are huge one day are forgotten the next. Seldom do reporters’ or columnists’ legacies live on beyond their retirement, let alone their death. One of the few exceptions to this is Mencken, and deservedly so. Mencken was not just a talented memoirist and scholar of American English but also one of the eminent political writers of his time. Admittedly, many of his judgments did not hold up: Mencken had many of the racial prejudices of his time, and his loathing for Franklin D. Roosevelt has not exactly been vindicated by history. However, this collection of articles covers the vulgar and hypocritical parade of politics during the Roaring ’20s, when Prohibition was the nominal law of the land. The 1924 election of Calvin Coolidge (of whom Mencken wrote, “It would be difficult to imagine a more obscure and unimportant man”) may be justly forgotten today. But it produced absurdities, such as a Democratic National Convention that required 103 ballots to deliver a nominee who lost to Coolidge in a landslide, that were ripe for Mencken’s cynical skewering. Today, his writing serves as a model of satire worth revisiting. — Ben Jacobs

From our list: The five best books to read before an election

Out Next Week

📚 Stranger Than Fiction: The Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel, by Edwin Frank

📚 An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth, by Anna Moschovakis

📚 Family Romance: John Singer Sargent and the Wertheimers, by Jean Strouse

Your Weekend Read

Don’t Turn Inward

By Julie Beck

Self over others, or at the very least self before others, has long been a prominent aspect of American culture—not always to Trumpian levels, certainly, but individualism for better and worse shapes both the structure of society and our personal lives. And it will surely shape Americans’ responses to the election: for the winners, perhaps, self-congratulation; for the losers, the risk of allowing despair to pull them into a deeper, more dangerous seclusion. On Election Day, the Times published an article on voters’ plans to manage stress. Two separate people in that story said they were deliberately avoiding social settings. To extend that strategy into the next four years would be a mistake.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.