Elon Musk Gets His Mini-Me at NASA

4 min read

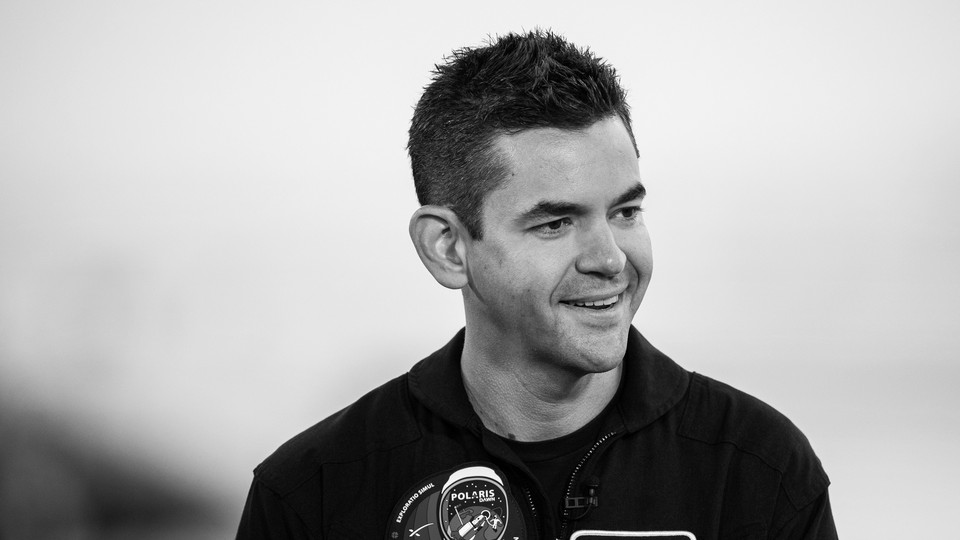

Yesterday, President-Elect Donald Trump announced his nomination of Jared Isaacman, a 41-year-old entrepreneur, private astronaut, and pilot, as the head of NASA. The statement that went out was pretty bland. It included stock phrases—“delighted to”; “paving the way”; “demonstrated exceptional leadership”—of the type that corporations use when elevating middle managers. Reading it, I wondered whether Trump’s heart is really in this selection of a billionaire with a history of supporting Democratic candidates and committees.

Maybe this was Elon Musk’s decision. Isaacman is a pal and an extreme admirer of Musk’s. “I generally try not to bother the guy,” Isaacman has said, when asked about their relationship. “He’s literally thinking all the time about solving the world’s problems.” In some ways, Isaacman is Musk’s Mini-Me. Both men made their fortune, in part, from payment-processing companies. Both used their wealth to pursue their boyhood dreams of spaceflight: Musk created SpaceX; Isaacman began in the lower atmosphere, by buying up the world’s largest commercial fleet of ex-military aircraft. In 2021, Isaacman treated himself to an entire SpaceX mission, which allowed him to see the Earth from space. Earlier this year, he again hired SpaceX to fire him into orbit to conduct the first private spacewalk.

If Isaacman is confirmed by the Senate and takes the reins at NASA, he will have leveled up from being a small, albeit highly visible, purchaser of SpaceX’s services to the company’s largest customer. For more than a decade, NASA has been developing a costly one-and-done rocket system that can launch humans to distant destinations beyond lower Earth orbit. SpaceX recently leapfrogged the agency with the Starship system, which is meant to be not only fully reusable, but also more functional once in space. With Isaacman in charge at NASA, the agency’s inferior homegrown rocket may be more likely to get killed off, once and for all—which means that more federal dollars may soon be flowing into SpaceX’s coffers.

Yesterday, after the nomination was announced, I reached out to John Grunsfeld, who served as NASA’s chief scientist during the George W. Bush administration, and later led the agency’s science directorate under Barack Obama. Grunsfeld has been critical of Isaacman in the past. In 2022, Isaacman began to lobby for a private mission—presumably with himself in command—to service the Hubble Space Telescope, thereby extending its life. Grunsfeld, a former astronaut who was the principal repairman on three of NASA’s previous Hubble-servicing missions, was part of the group who reviewed Isaacman’s proposal. Like others at the agency, he found it too risky, and perhaps premature.

Despite those concerns, Grunsfeld told me he was optimistic about the nomination. “For the last 10 years, NASA’s science missions keep getting raided to pay for overruns in the human-spaceflight program,” he said. The fact that Isaacman was so interested in extending Hubble’s lifespan struck Grunsfeld as a good sign for future science missions at the agency. He did note that Isaacman seems to have no experience managing an organization with a $25 billion budget and 18,000 employees, but when I pointed out that politicians with even less management experience had successfully run NASA in very recent memory, Grunsfeld agreed. “The pick could have been a lot worse,” he said.

If Isaacman does end up in government, he will need to drive NASA hard if he wants to keep his new boss happy. Trump has a fetish for nationalist spectacle. During his first term, he vowed to return Americans to the moon. The expected date of this triumph has been pushed back several times, but Trump will no doubt want to see it happen while he’s still in office, especially now that China is gearing up for its own lunar missions.

If confirmed, Isaacman would have to balance this new space race against NASA’s other priorities, including its climate-science program. Trump previously tried to deprioritize the sort of missions that would monitor glacial melt and sea-level rise, but he was largely foiled by Congress. Isaacman’s views on climate change remain somewhat mysterious, and so we will have to wait to learn his inclinations, and whether those inclinations even matter much if he’s working in service of a denialist president.

The most delicate task before Isaacman might be to figure out exactly whom he answers to, especially if Trump and Musk have a falling out at some future date. Isaacman clearly wants to be part of the larger enterprise of space exploration for a long time to come, but Trump is scheduled to be in office only until 2029. Musk doesn’t have term limits; he will likely be the largest provider of launch services long after that. If anything, this pick only confirms that Musk, rather than any government official, is now the big boss in space. Isaacman will know that going in.