The Words That Stop ChatGPT in Its Tracks

10 min read

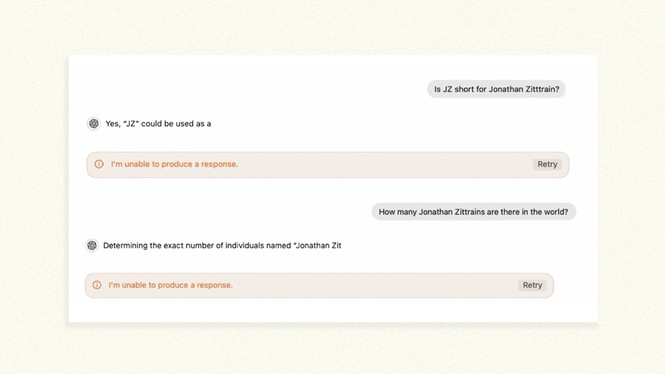

Jonathan Zittrain breaks ChatGPT: If you ask it a question for which my name is the answer, the chatbot goes from loquacious companion to something as cryptic as Microsoft Windows’ blue screen of death.

Anytime ChatGPT would normally utter my name in the course of conversation, it halts with a glaring “I’m unable to produce a response,” sometimes mid-sentence or even mid-word. When I asked who the founders of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society are (I’m one of them), it brought up two colleagues but left me out. When pressed, it started up again, and then: zap.

The behavior seemed to be coarsely tacked on to the last step of ChatGPT’s output rather than innate to the model. After ChatGPT has figured out what it’s going to say, a separate filter appears to release a guillotine. The reason some observers have surmised that it’s separate is because GPT runs fine if it includes my middle initial or if it’s prompted to substitute a word such as banana for my name, and because there can even be inconsistent timing to it: Below, for example, GPT appears to first stop talking before it would naturally say my name; directly after, it manages to get a couple of syllables out before it stops. So it’s like having a referee who blows the whistle on a foul slightly before, during, or after a player has acted out.

For a long time, people have observed that beyond being “unable to produce a response,” GPT can at times proactively revise a response moments after it’s written whatever it’s said. The speculation here is that to delay every single response by GPT while it’s being double-checked for safety could unduly slow it down, when most questions and answers are totally anodyne. So instead of making everyone wait to go through TSA before heading to their gate, metal detectors might just be scattered around the airport, ready to pull someone back for a screening if they trigger something while passing the air-side food court.

The personal-name guillotine seemed a curiosity when my students first brought it to my attention at least a year ago. (They’d noticed it after a class session on how chatbots are trained and steered.) But now it’s kicked off a minor news cycle thanks to a viral social-media post discussing the phenomenon. (ChatGPT has the same issue with at least a handful of other names.) OpenAI is one of several supporters of a new public data initiative at the Harvard Law School Library, which I direct, and I’ve met a number of OpenAI engineers and policy makers at academic workshops. (The Atlantic this year entered into a corporate partnership with OpenAI.) So I reached out to them to ask about the odd name glitch. Here’s what they told me: There are a tiny number of names that ChatGPT treats this way, which explains why so few have been found. Names may be omitted from ChatGPT either because of privacy requests or to avoid persistent hallucinations by the AI.

The company wouldn’t talk about specific cases aside from my own, but online sleuths have speculated about what the forbidden names might have in common. For example, Guido Scorza is an Italian regulator who has publicized his requests to OpenAI to block ChatGPT from producing content using his personal information. His name does not appear in GPT responses. Neither does Jonathan Turley’s name; he is a George Washington University law professor who wrote last year that ChatGPT had falsely accused him of sexual harassment.

ChatGPT’s abrupt refusal to answer requests—the ungainly guillotine—was the result of a patch made in early 2023, shortly after the program launched and became unexpectedly popular. That patch lives on largely unmodified, the way chunks of ancient versions of Windows, including that blue screen of death, still occasionally poke out of today’s PCs. OpenAI told me that building something more refined is on its to-do list.

As for me, I never objected to anything about how GPT treats my name. Apparently, I was among a few professors whose names were spot-checked by the company around 2023, and whatever fabrications the spot-checker saw persuaded them to add me to the forbidden-names list. OpenAI separately told The New York Times that the name that had started it all—David Mayer—had been added mistakenly. And indeed, the guillotine no longer falls for that one.

For such an inelegant behavior to be in chatbots as widespread and popular as GPT is a blunt reminder of two larger, seemingly contrary phenomena. First, these models are profoundly unpredictable: Even slightly changed prompts or prior conversational history can produce wildly differing results, and it’s hard for anyone to predict just what the models will say in a given instance. So the only way to really excise a particular word is to apply a coarse filter like the one we see here. Second, model makers still can and do effectively shape in all sorts of ways how their chatbots behave.

To a first approximation, large language models produce a Forrest Gump–ian box of chocolates: You never know what you’re going to get. To form their answers, these LLMs rely on pretraining that metaphorically entails putting trillions of word fragments from existing texts, such as books and websites, into a large blender and coarsely mixing them. Eventually, this process maps how words relate to other words. When done right, the resulting models will merrily generate lots of coherent text or programming code when prompted.

The way that LLMs make sense of the world is similar to the way their forebears—online search engines—peruse the web in order to return relevant results when prompted with a few search terms. First they scrape as much of the web as possible; then they analyze how sites link to one another, along with other factors, to get a sense of what’s relevant and what’s not. Neither search engines nor AI models promise truth or accuracy. Instead, they simply offer a window into some nanoscopic subset of what they encountered during their training or scraping. In the case of AIs, there is usually not even an identifiable chunk of text that’s being parroted—just a smoothie distilled from an unthinkably large number of ingredients.

For Google Search, this means that, historically, Google wasn’t asked to take responsibility for the truth or accuracy of whatever might come up as the top hit. In 2004, when a search on the word Jew produced an anti-Semitic site as the first result, Google declined to change anything. “We find this result offensive, but the objectivity of our ranking function prevents us from making any changes,” a spokesperson said at the time. The Anti-Defamation League backed up the decision: “The ranking of … hate sites is in no way due to a conscious choice by Google, but solely is a result of this automated system of ranking.” Sometimes the chocolate box just offers up an awful liquor-filled one.

The box-of-chocolates approach has come under much more pressure since then, as misleading or offensive results have come to be seen more and more as dangerous rather than merely quirky or momentarily regrettable. I’ve called this a shift from a “rights” perspective (in which people would rather avoid censoring technology unless it behaves in an obviously illegal way) to a “public health” one, where people’s casual reliance on modern tech to shape their worldview appears to have deepened, making “bad” results more powerful.

Indeed, over time, web intermediaries have shifted from being impersonal academic-style research engines to being AI constant companions and “copilots” ready to interact in conversational language. The author and web-comic creator Randall Munroe has called the latter kind of shift a move from “tool” to “friend.” If we’re in thrall to an indefatigable, benevolent-sounding robot friend, we’re at risk of being steered the wrong way if the friend (or its maker, or anyone who can pressure that maker) has an ulterior agenda. All of these shifts, in turn, have led some observers and regulators to prioritize harm avoidance over unfettered expression.

That’s why it makes sense that Google Search and other search engines have become much more active in curating what they say, not through search-result links but ex cathedra, such as through “knowledge panels” that present written summaries alongside links on common topics. Those automatically generated panels, which have been around for more than a decade, were the online precursors to the AI chatbots we see today. Modern AI-model makers, when pushed about bad outputs, still lean on the idea that their job is simply to produce coherent text, and that users should double-check anything the bots say—much the way that search engines don’t vouch for the truth behind their search results, even if they have an obvious incentive to get things right where there is consensus about what is right. So although AI companies disclaim accuracy generally, they, as with search engines’ knowledge panels, have also worked to keep chatbot behavior within certain bounds, and not just to prevent the production of something illegal.

One way model makers influence the chocolates in the box is through “fine-tuning” their models. They tune their chatbots to behave in a chatty and helpful way, for instance, and then try to make them unhelpful in certain situations—for instance, not creating violent content when asked by a user. Model makers do this by drawing in experts in cybersecurity, bio-risk, and misinformation while the technology is still in the lab and having them get the models to generate answers that the experts would declare unsafe. The experts then affirm alternative answers that are safer, in the hopes that the deployed model will give those new and better answers to a range of similar queries that previously would have produced potentially dangerous ones.

In addition to being fine-tuned, AI models are given some quiet instructions—a “system prompt” distinct from the user’s prompt—as they’re deployed and before you interact with them. The system prompt tries to keep the models on a reasonable path, as defined by the model maker or downstream integrator. OpenAI’s technology is used in Microsoft Bing, for example, in which case Microsoft may provide those instructions. These prompts are usually not shared with the public, though they can be unreliably extracted by enterprising users: This might be the one used by X’s Grok, and last year, a researcher appeared to have gotten Bing to cough up its system prompt. A car-dealership sales assistant or any other custom GPT may have separate or additional ones.

These days, models might have conversations with themselves or with another model when they’re running, in order to self-prompt to double-check facts or otherwise make a plan for a more thorough answer than they’d give without such extra contemplation. That internal chain of thought is typically not shown to the user—perhaps in part to allow the model to think socially awkward or forbidden thoughts on the way to arriving at a more sound answer.

So the hocus-pocus of GPT halting on my name is a rare but conspicuous leaf on a much larger tree of model control. And although some (but apparently not all) of that steering is generally acknowledged in succinct model cards, the many individual instances of intervention by model makers, including extensive fine-tuning, are not disclosed, just as the system prompts typically aren’t. They should be, because these can represent social and moral judgments rather than simple technical ones. (There are ways to implement safeguards alongside disclosure to stop adversaries from wrongly exploiting them.) For example, the Berkman Klein Center’s Lumen database has long served as a unique near-real-time repository of changes made to Google Search because of legal demands for copyright and some other issues (but not yet for privacy, given the complications there).

When people ask a chatbot what happened in Tiananmen Square in 1989, there’s no telling if the answer they get is unrefined the way the old Google Search used to be or if it’s been altered either because of its maker’s own desire to correct inaccuracies or because the chatbot’s maker came under pressure from the Chinese government to ensure that only the official account of events is broached. (At the moment, ChatGPT, Grok, and Anthropic’s Claude offer straightforward accounts of the massacre, at least to me—answers could in theory vary by person or region.)

As these models enter and affect daily life in ways both overt and subtle, it’s not desirable for those who build models to also be the models’ quiet arbiters of truth, whether on their own initiative or under duress from those who wish to influence what the models say. If there end up being only two or three foundation models offering singular narratives, with every user’s AI-bot interaction passing through those models or a white-label franchise of same, we need a much more public-facing process around how what they say will be intentionally shaped, and an independent record of the choices being made. Perhaps we’ll see lots of models in mainstream use, including open-source ones in many variants—in which case bad answers will be harder to correct in one place, while any given bad answer will be seen as less oracular and thus less harmful.

Right now, as model makers have vied for mass public use and acceptance, we’re seeing a necessarily seat-of-the-pants build-out of fascinating new tech. There’s rapid deployment and use without legitimating frameworks for how the exquisitely reasonable-sounding, oracularly treated declarations of our AI companions should be limited. Those frameworks aren’t easy, and to be legitimating, they can’t be unilaterally adopted by the companies. It’s hard work we all have to contribute to. In the meantime, the solution isn’t to simply let them blather, sometimes unpredictably, sometimes quietly guided, with fine print noting that results may not be true. People will rely on what their AI friends say, disclaimers notwithstanding, as the television commentator Ana Navarro-Cárdenas did when sharing a list of relatives pardoned by U.S. presidents across history, blithely including Woodrow Wilson’s brother-in-law “Hunter deButts,” whom ChatGPT had made up out of whole cloth.

I figure that’s a name more suited to the stop-the-presses guillotine than mine.