Nine Books About Aging, Growing, and Changing

10 min read

Living in a body is an exercise in enduring surprise and accepting change. During our lifetimes, we spring leaks, heal, grow, get sick, and age. We wake up some days and don’t recognize ourselves in the mirror. Some transformations appear on schedule—new rolls of flesh, sudden tufts of hair—and others come upon us suddenly: humbling bruises, unforeseen illnesses. But too frequently, we sanitize the moisture and mess of being alive with bland metaphors.

The best writing about our physical selves acknowledges that our exteriors affect how the world receives us; that we’re shaped and changed by family, friends, and lovers; and that as long as we’re alive, our bodies are always in flux. The nine books below are radically truthful: They explore moments of great change—pregnancy, puberty, illness, athletic training, weight fluctuations, aging, transition—and the revelations that accompany them. Reading them inspires both introspection and sympathetic reaction. You’ll wince in shared pain, sigh in relief, and remember that none of us stays the same for long.

A Very Easy Death, by Simone de Beauvoir, translated by Patrick O’Brian

In 1964, de Beauvoir published an arresting day-by-day account of her mother, whom she calls Maman, in her final month of life. Set during hospital visits and stolen hours at home, the book lays bare the physicality of approaching death, alongside the strange, stubborn tenderness nestled between a mother and her daughter. “No body existed less for me: none existed more,” de Beauvoir writes of the radical disorientation that her mother’s shrunken, nude form incites. Words become “devoid of meaning,” she observes, while touch, laughter, and facial expressions are a new language. In her last days, Maman finds freedom from the suffocating corset of her class and gender; de Beauvoir writes that she is able to experience “life bristling with proud sensitivities” and “no shame.” But her womanhood remains salient: In the hospital, de Beauvoir records how male doctors demean her mother, while nurses offer more compassionate care for her pain. Watching the woman who birthed her die leads de Beauvoir to fully understand how no body is permanent, and to reflect on how feelings and sensations can be passed down like eye color.

Heavy, by Kiese Laymon

Laymon’s memoir marks time through changing measures: weigh-in numbers, fat percentages. The book follows Laymon from childhood into adulthood, an alternately harrowing and healing journey in which the author must learn to listen to his body, even though American society has trained him to distrust, discipline, and punish it. Along the way, Laymon addresses binge eating, anorexia, overexercising, addiction, and sexual abuse. He learns early that as a Black man in a country designed to benefit thin, white, male bodies, American prejudice will bear down on him no matter how much he changes his appearance. Even when Laymon has starved himself down to his lowest weight, his mother reprimands him for considering going for a run at night, telling him, “To white folk and police, you will always be huge no matter how skinny you are.” In another revelatory moment, he writes that the number on the scale has long been “an emotional, psychological, and spiritual destination.” But with every lost pound, the psychological weight of that number grows heavier. When his weight loss spirals into disordered eating, his body knows before his mind does that he is heading somewhere dangerous. In the end, he can only escape that destination by turning toward the women who raised him, and by paying attention to the wisdom of his own form.

The Hearing Test, by Eliza Barry Callahan

When a young musician wakes one day with “rolling thunder” thrumming through her head, her life whittles quickly into a case study. Experts are called in; appointments are arranged; doses are prescribed. She learns she’s suffering from encroaching sudden deafness, and she’s told she must enter trials, attempt hypnosis, cut out many of her favorite foods, and avoid too much stimulation, sex included. This engrossing, eccentric novel ties together our ideas about time and sensation, revealing how illness alters both. Then it untangles that knot and weaves a linguistic fabric unlike any you’re likely to have felt before. After losing her hearing, the narrator reaches outward, reflecting on the uncanny coincidences in her life and the lives of those she loves. She writes obsessively about artists who greeted bodily change with grace, and burrows deep into their projects. She finds inspiration in an internet forum for people who have also been abandoned by their senses, where members make earnest attempts to understand their new worlds. The novel finds succor in the shared experiences of shifted perception: Loss of one sensation inspires journeys through others, or leads to the solace of discovering others with similar struggles.

King Kong Theory, by Virginie Despentes, translated by Stéphanie Benson

This polemic unfurls in vitriolic vignettes that inspire righteous fury. Despentes, a feminist French filmmaker and writer, takes on beauty ideals, rape, and aging, invoking the figure of King Kong—something “on the link between man and beast, adult and child, good and bad”—to imagine a kind of womanhood that claws back at cruel, unfair patriarchal standards. She begins by defending “the loser in the femininity stakes,” attempting to rescue girls from the wreckage of a society that measures their bodies against impossible ideals. In livid but conversational prose, she unveils the way beauty standards and sexual violence are parallel exercises of power, and argues that patriarchy not only wants women in pain but also demands that they hide that pain––teaching women to feel shame rather than rage when hurt. Despentes details how her own sexual assault was a process of disempowerment; she learned to resist that feeling through speaking about her pain, and through decorating and dressing herself according to her own tastes. And as she ages, she sees how society demands that older women not draw “too much attention”—and gleefully refuses, calling for all women to take pride in their changing forms. In a world that tells women to “conceal your wounds, ladies, lest they upset the torturer,” Despentes wants us to wear our scarred skin with pride, as evidence of our animal persistence.

Lament for Julia, by Susan Taubes

A specter stalks a girl—or saves her life—in this ephemeral, mystical novella, first published 54 years after Taubes’s death. The nameless spirit, for reasons unknown, is inextricably linked to its charge, a child who becomes a woman in “a transformation so mysterious and violent,” it must at times avert its eyes. The being and the reader observe Julia’s journey through the great bodily changes of puberty, when she awakes horrified and afraid by the bloodstains in her bed, and pregnancy, when Julia’s entire sensory world is rendered “exquisite and suffused with the odor of souring milk, blood, urine and excrements.” These changes alternately entrance and disgust Julia’s guardian angel, but the ghost is most disconcerted, and eventually outraged, by her gradual adoption of archetypically feminine behaviors. In the process, she’s hiding away her wild interior, which it knows to be her most genuine, embodied self: Was there even “such a thing as woman? I began to doubt it,” it thinks. Lament for Julia turns a strange, searing, and subversive eye toward the universal process of self-construction, and the ways social demands usurp women’s agency as they mature.

I Heard Her Call My Name, by Lucy Sante

Sante’s book opens with a bombshell—and a play on words. The bombshell first appears to be Sante’s announcement of her gender transition to her social circle via email. But it’s also, she jokes, herself: a beautiful woman. I Heard Her Call My Name is a coming-of-age tale that, like all stories about puberty, involves hormones and hair along with nerves, terror, and unexpected euphoria. Sante, a prolific writer and artist known for her memoirs and criticism, documents her late-in-life series of bodily changes, connecting that metamorphosis to her adolescent puberty, sexual awakenings, and the experience of aging into her 60s. She begins in youth, finding a “distinct rhyme” between gender transition and her childhood move from Belgium to the United States. But they’re not entirely analogous: Although the facts of her citizenship are initially rigid, the femininity Sante finds via transition is atmospheric; it is a way “of seeing the world, of organizing place and time, of the urge to give, of connectedness to others,” even as it involves injections of hormones, softening skin, new hair, and a novel tenor of voice. The book reminds us to trust our physical impulses, and demonstrates how change can take us to more liberated places than we’ve managed to find before.

Read: Young trans children know who they are

Easy Beauty, by Chloé Cooper Jones

This memoir combines aesthetic theory, philosophy, and personal writing to create a story of self-discovery, predicated on reconceptualizing “beauty.” Cooper Jones was born with a rare disability that renders her physical form surprising to most observers, so she’s locked out of what she calls “easy beauty”: symmetrical, simple, and legible according to entrenched standards. Her condition also means she experiences near-constant pain, which “plays a note I hear in all my waking moments,” she writes. But in her book, Cooper Jones opens up to new sensations and startling epiphanies as she teaches herself to take up space without shame and to stare back at those who dare to judge her. In turn, she finds unexpected possibilities for and sources of beauty—in crowded concerts and people moving through a museum, in watching her son’s skeleton and organs develop during her pregnancy. Seeing him in a sonogram, she writes that she is “pulsing around him, my blood, my skin, wrapped around a void” of pure potential. Through her writing, beauty becomes a moving, muscled, amorphous thing. It’s a body that loves and is loved, that builds other bodies and is unafraid to bend into the unknown.

The Undying, by Anne Boyer

Boyer’s book on breast cancer is at once a group memoir, a history of a personal tragedy, and a story of violence masquerading as medicine. At age 41, Boyer was diagnosed with one of the deadliest forms of breast cancer, and embarked on an excruciating, financially draining, and devastating treatment journey—but found herself in a sorority of other women who’d been through the same thing. A litany of breast-cancer survival stories miscast healing as an individualistic fable “blood pink with respectability politics,” she explains, but her memoir of diagnosis and treatment resists this framing. Instead, Boyer directs her anger toward the polluting systems that can cause cancer and the medical establishment that treats it expensively and painfully. She argues that people cannot be solo actors in pursuit of health when our world is full of carcinogens, and she rejects medical narratives that inspire shame in the ill while draining their bank accounts. In one rousing moment, she and her patient-peers reject toxic positivity in a chemotherapy room, speaking up about the pain of their treatments rather than enduring it in silence. This is part of her attempt to use her body, and her story, to change our understanding of cancer from an individual struggle to a collective one, and to forge solidarity among those it touches.

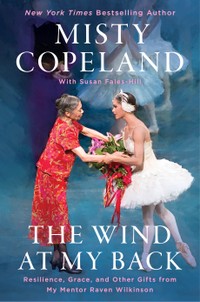

The Wind at My Back, by Misty Copeland with Susan Fales-Hill

Copeland’s memoir is a tale of endurance and athleticism, awe-inducing feats of motion and perseverance through mental and emotional pain. The world-famous ballerina, and the first Black principal dancer in American Ballet Theatre history, makes her book a love letter to her mentor Raven Wilkinson, another Black ballerina, who died in 2018. In the 1940s, Wilkinson decided she would be willing to “die to dance,” which she almost did––performing across the country despite violently enforced segregation laws in the South. By the time she and Copeland embarked on a friendship, Wilkinson had retired and fallen into obscurity; Copeland was furious to learn that a fellow Black ballerina had been erased from the discipline’s history. Learning from her “was that missing piece that helped me to connect the power I felt onstage to the power I held off it,” she writes. Copeland wrings meaning from the toll that dance takes, recalling “wrecked” muscles and toes “cemented in my pointe shoes.” Dance influences how she writes about physical transformations, including pregnancy—she calls her son’s kicks “grands battements.” Wilkinson’s wisdom about dance, aging, exhaustion, and exertion puts Copeland’s own struggle against ballet’s racism into historical relief. Ultimately, their pas de deux underscores the power of the art their bodies forge.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.