The Slyest Stroke in Tennis

6 min read

For my 34th birthday, in 2015, I received two tickets to the men’s quarterfinal of the French Open. I’m a Rafael Nadal loyalist, and I hoped to cheer for the King of Clay. I ended up seeing the Swiss-on-Swiss pairing of Roger Federer and Stanislas Wawrinka. This turned out to be a mercy, because I missed Novak Djokovic become only the second man ever to defeat Nadal at Roland-Garros, and was treated instead to some of the most beautiful groundstrokes I have ever seen.

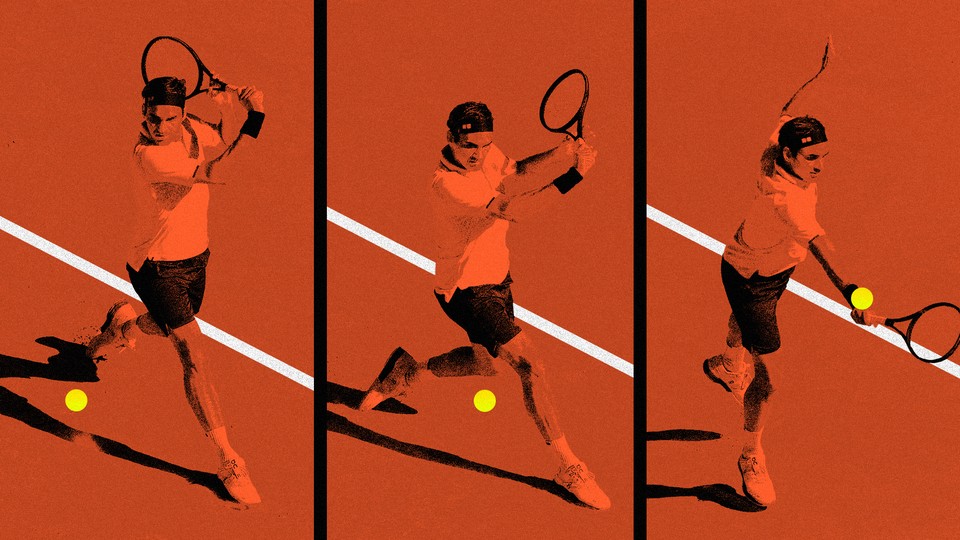

Wawrinka, who would go on to upset Djokovic in the final, was playing the best tennis of his life, stretching the court to open up Pythagorean angles. What struck me most about that match, other than the straight-set ease with which Wawrinka subdued a 33-year-old Federer—then still widely considered the greatest in the game—was the aesthetic mirroring of their backhand play. Both Federer and Wawrinka opt for a single-handed grip, which led to a number of exquisite backhand rallies the likes of which a contemporary fan almost never gets to enjoy.

The French Open is the most eccentric of the slams, played on an impractical surface of ground brick that must be raked and swept and alternately moistened and kept dry. Conditions shift with the fickleness of the Parisian thermometer, and points are drawn out from the slower bounces. The main court, Philippe-Chatrier, is far smaller and more intimate than Arthur Ashe Stadium, in Queens, and the players, smudged with sweat and dirt, appear human and vulnerable as they lunge and slide across the burnt-sienna stage.

At 2–2 in the third-set tiebreak, Wawrinka served down the center to Federer’s deuce court. Federer returned cross-court with his balletic single-handed backhand, to which Wawrinka responded with a forehand. Federer ran behind the ball and whipped a forehand cross-court again, to Wawrinka’s masterful single-handed backhand. They exchanged eight strokes this way, holding each other in check, until Federer sliced a backhand again, changing the rhythm just enough to allow Wawrinka the chance to disguise an identical-looking backhand that shot instead directly down the deuce-court line. A defeated Federer doubled over, hanging his head.

What is so compelling about the one-handed backhand is the way a talented player can use the motion, especially on the run, to conceal until the last possible moment the direction of his shot. Power and consistency aren’t the only skills involved; there’s also subterfuge, and therefore artistry. More than any other stroke in tennis, the one-handed backhand is as good as the player using it. Its value rests on their ability to veil intent, change direction and pace, and foresee unusual angles. In other words, it is more dependent on a player’s creativity than on his strength. It becomes a kind of signature that no one else can forge.

The shot, sadly, is almost obsolete. A few days ago, Le Monde published a “Requiem for the One-Handed Backhand, Emblem of Romantic Tennis.” “Here lies the one-handed backhand, the Apollo that lovers of beautiful play thought immortal,” the writer laments. So far this year, just two players ranked in the top 10—Stefanos Tsitsipas at No. 9 and Grigor Dimitrov at 10—have used a one-handed backhand, the fewest since records have been kept. Flamboyance, artistry, the elaborate and improvisational construction of points through varied technique—have been subsumed by the supreme value of efficiency.

A two-handed backhand is certainly more efficient; it’s essentially another forehand, generating superior pace and control. Improvements in racquet technology and strength training have allowed tennis to evolve into a contest of power-hitting and baseline defense, and a two-handed grip better protects a player from deep balls bouncing high above the waist. Federer’s reliance on the single-handed backhand is one reason he struggled so mightily against the loopy topspin of Nadal, who—truly we will never see his kind again—plays like a lefty though he’s actually right-handed. It is also why, with what is probably the most effective two-handed backhand in the history of the game, Djokovic became the winningest man in tennis of all time.

And yet, winning isn’t quite everything. (And this is not a denial of Djokovic’s dominance—I concede.) Fans respect and honor margins of statistical superiority, but when the balance tips too far away from style, we can’t help but feel depleted. Here lies the realm of the inhuman. This is why so few basketball fans outside San Antonio ever fell in love with the Spurs under Tim Duncan. If efficiency were all that mattered, we would be interested in the chess played only by Stockfish and AlphaZero.

In fact, the world of chess exemplifies the bleakness of allegiance to efficiency. Computer analysis has homogenized the game seemingly irreversibly. The intuitive brilliance of previous grandmasters such as Paul Morphy and Bobby Fischer would wither today before the irrefutable “number-crunching,” as Garry Kasparov called it, of players trained through the computer’s lens. All the top players spend months preparing for each tournament, studying with the aid of computers to identify the slightest positional advantage. The former world champion Viswanathan Anand once told The New Yorker, “Every decision we make, you can feel the computer’s influence in the background.” The highest-ranked chess player of all time, Magnus Carlsen, recently decided not even to defend his title in the world championships. One reason, he admitted, was that he no longer thinks the tournament is any fun.

This preference for brute efficiency has become the defining characteristic across practically every field of human endeavor. Verve and idiosyncrasy are indulgences. Even an unguardable move such as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s iconic “skyhook” would lose its luster in today’s money-balled NBA, where the statisticians have proved that the smartest way to play involves enormous quantities of three-point shots. There have perhaps never been more talented athletes and marksmen and less variety of gameplay. Everyone leverages the same generic (if often impressive) step-back three. Whereas human ingenuity and beauty flourishes within the framework of constraint, the fact that these deep shots are even more effective when a player shuffles in a third step—i.e., when he travels—has only meant that the rules themselves have had to be ignored to accommodate the innovation.

With the advent of artificial intelligence, the efficiency bias looms everywhere. In the field of illustration, how long will the frail human hand, no matter how deft, be able to compete? What about journalism? The media company Gannett is experimenting with AI-generated summaries at the top of articles so that savvy readers can eschew the burden of considered and structured text and receive bullet-point briefings in its place. Even when it comes to literal romance, where one might be forgiven for believing that romantic gestures ought to remain safe, Whitney Wolfe Herd, the founder of the dating app Bumble, speculated that the future of dating will involve AI “concierges” meeting with other AI personas to set their eponymous humans up on dates. “There is a world where your dating concierge could go and date for you with other dating concierges,” Wolfe said. “And then you don’t have to talk to 600 people.”

In a March interview with GQ, a reporter mentioned to Federer that, at that moment, not one men’s player in the top 10 used a single-handed backhand. “That’s a dagger right there,” Federer replied. “I felt that one. That was personal.” Widely considered to have epitomized the aesthetic possibilities of the game while—for a time at least—accumulating more titles than had ever been thought possible, Federer’s career was proof that an all-around skill set can be both highly efficient and profound.

And yet, in that same conversation, even he admitted to teaching his own children to hit the ball with two hands. He was, he confessed, “a bad custodian of the one-hander.”