The Disaster That Shook America’s Secular Faith

10 min read

The modern world runs on a kind of secular faith. Most of us turn on the faucet and expect water, enter an elevator and expect it to take us to our destination, drive over a bridge and expect it to hold up beneath us. Airplanes make this conviction especially visible. Although American aviation is incredibly safe, fear of flying is a widespread, well-known anxiety: Some people just can’t quite stomach hurtling unnaturally through the air, seven miles above everything familiar. But for the large majority of those who travel on planes,trust supersedes these fears—or they just don’t think that hard about it.

In January, though, a door plug that appears to have been improperly installed flew off at 16,000 feet, tearing a hole in the side of a plane. That same month, two aircraft collided on a Japanese runway, resulting in a huge fire. Social media and news articles described how a landing-gear tire fell from a plane and crashed in a parking lot; an engine cowling blew away during takeoff; two weeks ago, one flight’s violent turbulence resulted in a death and dozens of injuries. Suddenly, passengers unaccustomed to thinking about how planes stay up began to panic. Although aviation experts and journalists were quick to reassure the public that planes are built with multiple safeguards and that pilots are trained for emergency scenarios, a bit of the magic had vanished.

This same stunning disillusionment happened on the morning of January 28, 1986, when the American public watched the Space Shuttle Challenger rise into the sky and then disappear in a cloud of white vapor. But first came the confidence, which had been inspired and stoked by two decades of human spaceflight preceding this mission. This belief was also undergirded by a trust in American ingenuity and in the unstoppable march of technological progress. And no one seemed to embody this faith better than the American teacher and astronaut Christa McAuliffe as she lay in her place on the orbiter’s middeck, waiting for liftoff.

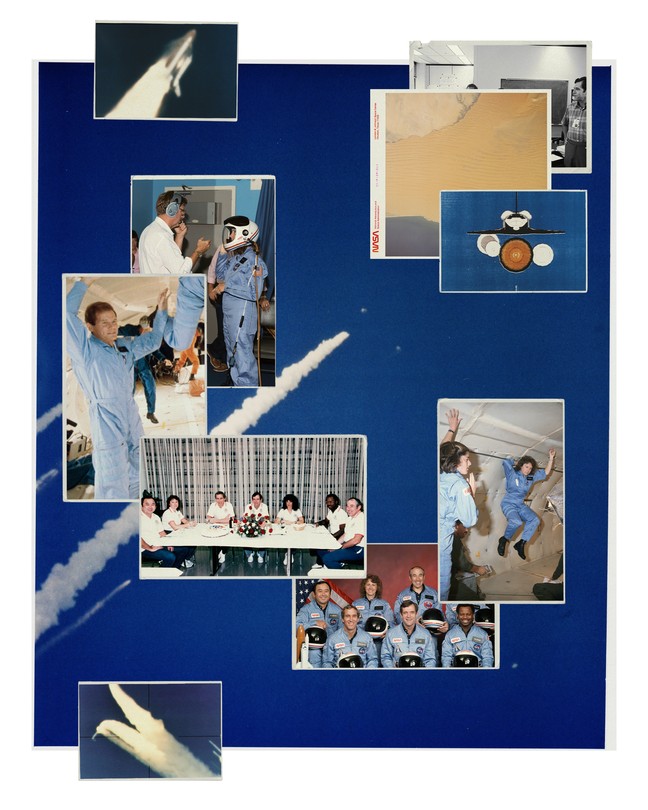

She was one of seven astronauts on the doomedflight, but McAuliffe’s name is the enduring symbol of the disaster, because she was not a scientist or an engineer; she was a regular person chosen specifically to be the inaugural “Teacher in Space”—our ambassador to the stars. Of the six other crew members, one, Gregory Jarvis, was a civilian brought along to conduct experiments on fluid dynamics. The rest were career astronauts; among them were Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, and Judith Resnik, pioneers in diversifying NASA’s astronaut corps. In addition to McAuliffe, two others on board, Jarvis and Michael Smith, would be going to space for the first time; McNair and the mission commander, Dick Scobee, had flown on Challenger before.

Although NASA had successfully ferried people to space and back nearly five dozen times, there was still a significant amount of risk in what they were doing—each crew member knew that. But in July 1985, McAuliffe sat down with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. Two days before, Challenger had had a thorny launch; while it blasted off, a malfunction had forced one engine to shut down and threatened a second. Without enough thrust to make it to their planned height, the crew was forced to bail out to a lower orbit of Earth. “Are you in any way frightened of something like that?” Carson asked. “Because just the other day … they had a frightening lift.” “Yes,” McAuliffe replied. “I really haven’t thought of it in those terms, because I see the shuttle program as a very safe program.” When the British journalist Adam Higginbotham relates this anecdote in his stunning new book, Challenger, he notes that she was answering as she was expected to: Part of her deal with NASA was to make calm, composed media appearances to spread the good word about the American space agency. But she was also game. The night before everything went wrong, waiting to hear if her mission would go ahead, she told her friend, “I still can’t wait.”

She had faith, essentially. Examined closely, it could be described as a belief that the engineers who’d designed the ship’s complex components knew what they were doing; that the manufacturers responsible for assembling them did so correctly; that the crews responsible for repairs and maintenance—fueling and insulating the external tank, repairing the orbiter’s heat-resistant tiles—performed their jobs fastidiously; that Scobee and Smith in the cockpit would fly with experience and precision; that Mission Control would give commands wisely and safely; that any problems found would be openly discussed and rectified. Everything depended on a wide, complicated system of human beings—and on the last point, they failed.

By the time the crew was on the launchpad on the morning of the 28th, their mission, officially deemed STS-51-L, had been scheduled and scratched multiple times in the previous six days for suboptimal conditions. “They don’t delay unless it’s not perfect,” McAuliffe’s husband had told TV reporters. This would be the 25th mission of a NASA space shuttle, and Challenger’s sister shuttle Columbiahad just returned from a six-day journey 10 days before. In classrooms across the country, approximately 2.5 million schoolchildren were watching satellite broadcasts of McAuliffe’s voyage. Routine launches promised to fulfill a long-held dream of a sort of taxi service to space: In 1972, President Richard Nixon had signed off on a “Space Transportation System,” which gave the missions their acronym, saying the U.S. should work to “transform the space frontier of the seventies into familiar territory, easily accessible for human endeavor in the eighties and nineties.” As a result, shuttle seats were no longer limited to just NASA’s rarified crews. Senator Jake Garn made his way onto a 1985 flight, with the controversial goal of overseeing what the government was paying for; NASA was mulling sending a journalist on a mission (Walter Cronkite was considered a front-runner). Space travel was, it seemed, on the cusp of becoming routine.

But the reader, reaching the moment 340 pages into the book when the crew is finally sealed into the orbiter, knows this dream won’t be fulfilled. And Higginbotham includes a horrifying moment of McAuliffe’s faith being shaken: The astronaut assisting them into place and finishing final preflight checks “lookeddown into her face and saw that her Girl Scout pluck had deserted her,” he writes.“In her eyes he saw neither excitement nor anticipation, but recognized only one emotion: terror.”

She would fly for 73 seconds before the shuttle broke apart in a fireball and a cloud of smoke. After that gut-wrenching instant, and more seconds of stunned silence, a NASA public-affairs officer would speak the understatement that would become famous: “Obviously a major malfunction.”

Higginbotham’s book, like his previous one, Midnight in Chernobyl, is a gruesome and meticulous reconstruction of a 1986 disaster. Challenger’s failure is a story of advanced technology that breaks down not because of an unforeseeable act of God, but because of utterly human failures. In this case, according to the Rogers Commission, hot gases snuck out of a joint of one of the shuttle’s two solid rocket boosters before synthetic rubber seals, called O-rings, could expand to close the gap. Flames from the booster burned the surface of the main fuel tank, where half a million gallons of liquid hydrogen and oxygen waited to ignite. The booster wrenched itself from the assembly and tore the ship apart. This happened because the O-rings were slow to expand and inflexible in cold weather. (The physicist Richard Feynman would show this in a televised post-event hearing through a devastatingly simple demonstration: dunking the material in a cup of ice water.) The morning of January 28 was below freezing in Cape Canaveral, Florida, and Challengerhad sat on the launchpad in such weather overnight.

The double O-rings had long been a problematic fix to a technical snag where two pieces of the rocket fit together. The joint had been inspired by a missile used by the Air Force; facing budget pressure for the first time in its existence, the space agency was compelled by “the imperative to invent nothing new,” as Higginbotham explains. Engineers at Morton Thiokol, the firm that designed and manufactured the rockets, added a second O-ring to enhance the original joint, among other modifications. Because they’d changed an existing technology, the company and their supervisors at the Marshall Space Flight Center, in Huntsville, Alabama, felt, according to Higginbotham, that they had only taken a known joint and made it safer—but they were really embarking on a dangerous trial of an untested technology, and the peril quickly made itself known. Issues were documented for years; multiple flights had potentially catastrophic damage that became apparent only after the boosters were recovered and examined. By January 1985, a year before the Challenger explosion, Roger Boisjoly, a Thiokol engineer who “knew the O-rings better than anyone,” was telling his colleagues that low temperatures were likely to cause leaks that could cause a total loss of mission, crew, and vehicle.

So the O-ring problem was known at Morton Thiokol. It was also known at Marshall, home of NASA’s rocketry hub. And it was certainly known at the Kennedy Space Center, in Florida, where the launch would happen: The night before the tragedy, there was a three-way conference call among Thiokol in Utah, specialists in Huntsville, and the NASA team in Cape Canaveral, where Thiokol engineers laid out a step-by-step case against going ahead the next morning, outlining the dangers of launching with O-rings colder than 53 degrees Fahrenheit. But NASA pushed back. The team argued that the data weren’t strong enough to establish that air temperature on its own was a significant contributor to seal problems, Higginbotham details; they pointed at a flight with particularly bad leakage launched in warmer temperatures, and four test motors that fired in the cold without issue. Morton Thiokol’s leaders took a caucus. It was time to make a “management decision,” they said. Half an hour later, they got back on the call and told the group they’d changed their minds. The company was asked to—literally—sign off on the launch, the book explains, contravening the typical convention of an oral poll on whether or not to move forward. It had been decided that the launch lay within the boundary of acceptable risk.

The engineers, including Boisjoly, felt crushed. They’d assembled a last-minute presentation to try to avert a crisis; they had been overruled without the gathering of any new evidence to contradict their finding. Perhaps individual Thiokol representatives had a desire to please the firm’s billion-dollar client or to keep the shuttle schedule on track. Maybe they just didn’t want to make waves. But the astronauts had no idea that this had even happened when they made their way into the orbiter that morning. Like the American public watching at home, they were convinced that their spaceship would fly.

Higginbotham’s book is full of heart-stopping moments like these—the kind that make a reasonable person shout, “Oh, God, how did they let this happen?” Such events begin decades before Challenger, going back to 1967, when Apollo 1 caught fire on a launchpad, killing three astronauts … after NASA leaders had been warned about the capsule’s faulty wiring and the huge amount of flammable nylon and Velcro inside. More than a decade later, efforts to add an emergency-escape system to the space shuttle fizzled, in part to avoid the public perception that the shuttle was unsafe, the book alleges. Higginbotham later suggests that some of the Challenger crew may have been alive for about two minutes as the crew compartment plunged toward the ocean—but with no way to eject, even though that may not have saved them after such a dramatic failure.

In just the five years that the space shuttle had been operational, the window of tolerated risk inside NASA and among its contractors kept getting wider and wider, Higginbotham exhaustively shows. A great and lurching bureaucracy was trying to match the promise and expectations of the 1960s under the slimmed budget and pro-privatization, anti-government attitudes of the ’70s and ’80s. So rockets that had serious flaws were marked safe for human flight. The burden of proof in flight-readiness reviews seemed to shift in the period before Challenger, Higginbotham suggests, from having to show that a given flight was safe to proceed to having to convincingly demonstrate that it wasn’t—as shown in that disastrous meeting the night before launch, when Thiokol could not make its data prove that the launch would fail.

And it’s stomach-churning to read about the fragility of the orbiter’s heat-resistant tiles, or for Higginbotham to casually reference the foam insulating the shuttle’s external tank, knowing what would happen nearly two decades after Challenger. In 2003, a chunk of foam fell off the tank of the Space Shuttle Columbia as it was lifting off, and hit the orbiter’s wing. Like the O-rings, “foam strikes” were a known problem during launches, documented since the program’s first flights, and the delicacy—and importance—of the heat shield was equally well known. But by this point, loose foam seemed fairly routine, and the impact failed to drum up much alarm at Mission Control. More than a week later, Columbia tried to return to our planet, but the hole that chunk had made in the heat tiles was fatal. The orbiter came apart, killing everyone on board.

These issues—faulty O-rings, foam strikes—were understandable. Theoretically, with study and ingenuity, they were fixable. The problem was not really a lack of technical knowledge. Instead, human fallibility from top to bottom was at issue: a toxic combination of financial stress, managerial pressure, a growing tolerance for risk, and an unwillingness to cause disruption and slow down scheduled launches.

Challenger is a remarkable book. It manages to be a whodunit that stretches hundreds of pages, a heart-pounding thriller even though readers already know the ending. The passion and ideals at the heart of human spaceflight come through, which only adds to the tragedy of understanding how many chances there were to save the astronauts aboard. Our faith in the systems that run our world is really faith in our fellow man—a chilling reality to remember.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.